Issue 6

Time

the indefinite continued progress of existence and events, past, present, and future

A friend of mine was telling me he wanted to slow down and do less and enjoy life. I agreed that I wanted to slow down but not do less. I want to do more. More of the things that matter, spending more time with my friends and loved ones, creating more designs and images that matter, and not having my time filled with meaningless busy work that doesn't matter. I know we have to do busy work, as I call it. I tell my students that as a creative you get to be creative 10% of the time and the rest of the time is doing things that support and make that 10% of creativity.

I long for an existence outside of time when I am not worried if I have enough or if I will finish the project-being cut short by the setting sun. The fact is, there is always more time. Maybe not for me, my garden, or my pets, but there is always more time. Time will march on with or without us.

Time is one of the great intricacies of photography that creates the image. The moment you take the photo, it is about the present time. After the photo is taken, it lives in the future but is from the past. Not many art forms are so conscious of the moment, the past, and the future all at the same time.

Time leaves a mark on our bodies and plays tricks with our minds. The wisdom that only comes with time, the wine or whiskey that grows more valuable with age, the silver-lined crown of the queen, like a soup that grows more tasty the following day, the parade of color from the garden that only time can coax into bloom, and yet it's time that can only heal the broken hearted.

When I think of time, I consider places like Paris, Rome, and Prague, because they have seen so much time go by yet some things have remained the same. This reminds me that we live in a small speck of time through history, which makes me think of all the time after me as well. I think of grandparents who are gone and great-grand-parents that I never knew, my kids and my grand and great-grandchildren that I will never know, and what I leave behind for them.

When I think of time it stretches my imagination and challenges my brain to seemingly think outside of its confines.

There never seems to be enough of it, although we have all the time in the world.

I often take inventory of how my time is spent and how I can construct a more enjoyable life.

STITCHING A LIFE

Text by Donna Steel + Photography by Robert Rausch

The inherited machine, a sturdy Pfaff in a mid-century cabinet hadn’t changed, though it had changed hands.

Metal mechanics humming,

foot pedal pressing,

Tension taut, but forgiving,

Needle thread

Up looping bobbin thread down,

Resurrected to connect

top to bottom

Front to back

Side to side.

She sewed seams straight,

guided with patience,

making the line

that is the seam,

that joins the edges,

Edges trimmed with pinking shears that also made paper birthday hats,

A felt Christmas stocking,

a Valentine's heart.

She is dusty, now, as the machine,

unable to fix mistakes,

repair frayed edges,

frayed daughters,

She is buried, now,

deep as the needle,

up then down,

Daughter knowing, now, what sewing straight means,

What an easy pattern for a dress,

for a life,

Makes the edges meet

Front to back,

Top to bottom,

Side to side,

Mother to daughter.

ANQUETIN

On the Street At Five in the Afternoon

Text by Lynne Berry

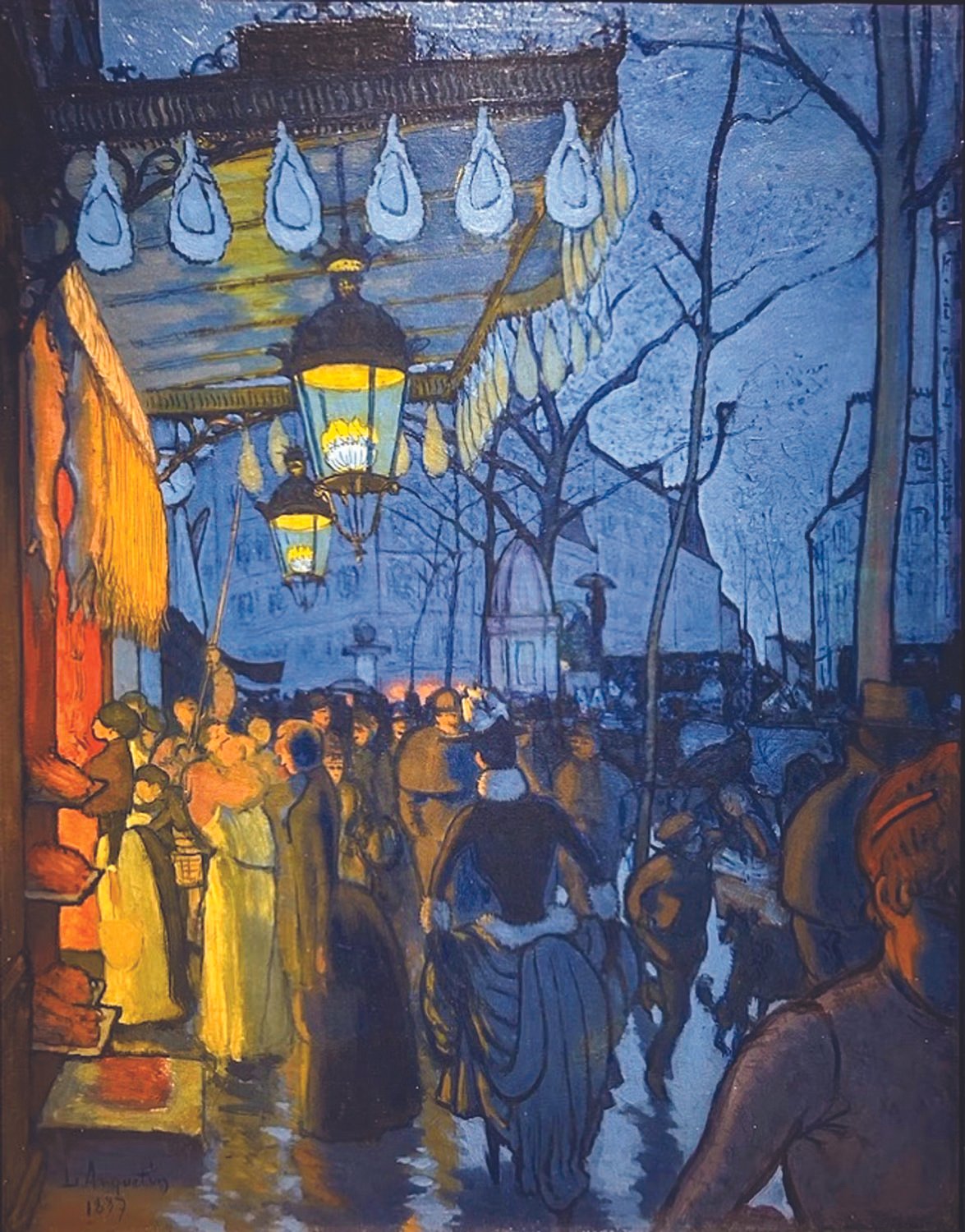

Street at Five in the Afternoon by Louis Anquetin is predominantly blue, over three-fourths blue. And there is only one blue. It is as if he had a tube of a certain color blue and he mixed it with varying amounts of white for almost everything in the painting — the sky, of course, the buildings, the crowd, the trees.

This is that magical moment on certain cold winter days when, if you are paying attention, your breath can catch as you realize that darkness is falling. It’s not yet completely dark but it’s far from light. It’s that almost surreal time when you might look across the street for someone and not quite be able to recognize them — “Is that him? He’s about that size. He walks that way. But it’s murky, there are so many shadows, I can’t tell.” One moment later you would not have seen him at all.

Anguetin has captured this uncertainty well. Midway there are shapes that are clearly people including one well-dressed woman with a glorious hat who is holding up her skirt to keep it from getting dirty. Further right there are shapes that could be a boy, or a dog. Further to the right things get even more indistinct.

Then there’s the left side of the painting. I have read that he was depicting a butcher shop in his neighborhood, Montmartre, in Paris. It’s well-lighted with a reddish-orange storefront. It has the carcasses of some kind of bird hanging out front and there are other items on display on shelves to the left of the door. Some people are window shopping, some are entering. A gas-lighter has illumined two large hanging lamps with happy yellow flames. These beautiful lamps and the light pouring out from the shop window pick out some of the details of these shoppers – clothes, hairstyles, facial features. The shoppers make me think of moths drawn to a flame.

Other than the obvious subject, on the street at five o’clock in the afternoon, this painting is about warm and cool. You can feel the warmth, even the camaraderie and shared purpose (buying dinner) on the left side while the cool right side is colder, nebulous, uncertain, and perhaps even a little threatening.

All in all, though, this is a delightful late winter scene.

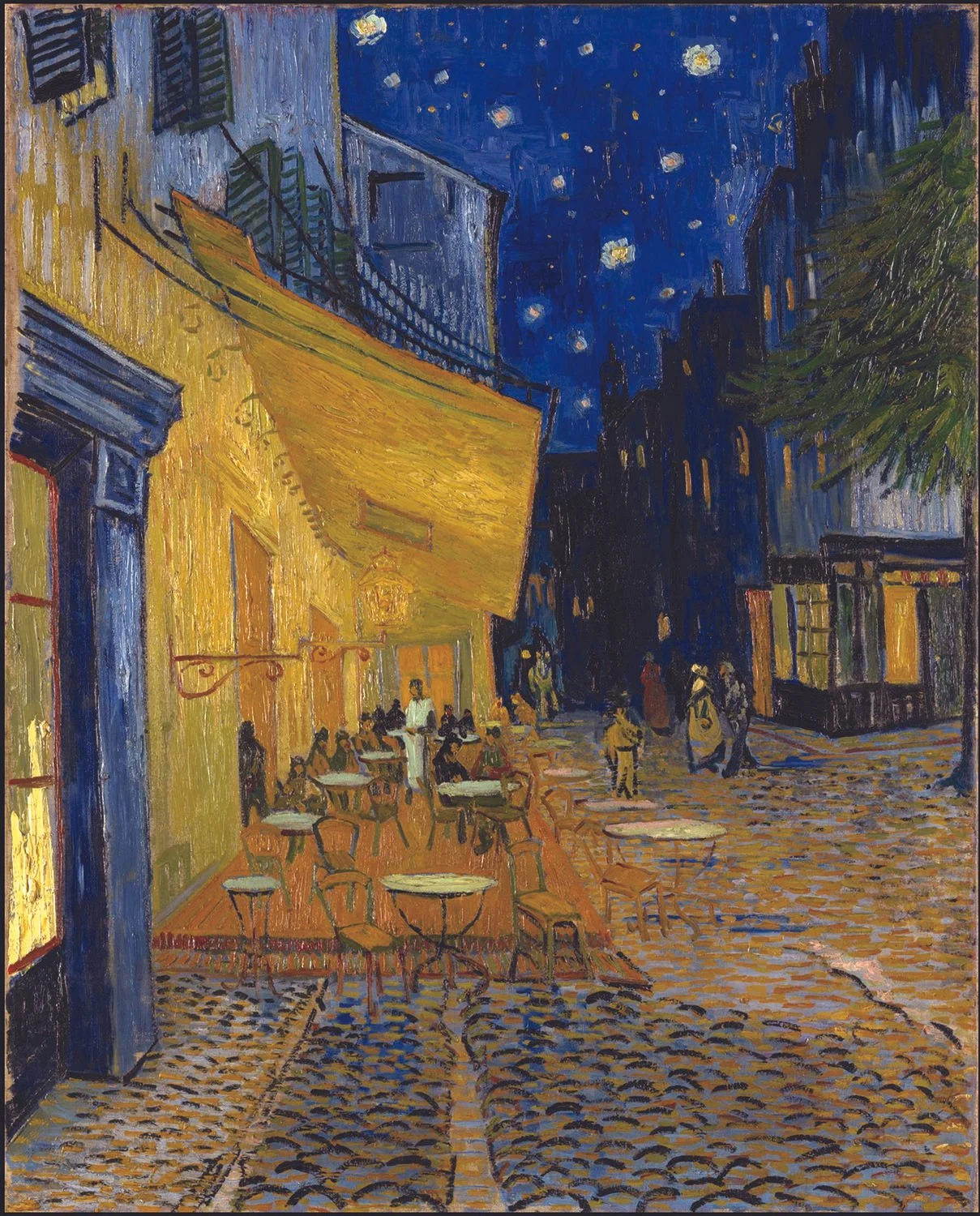

I couldn’t help thinking I’d seen something similar by Vincent van Gogh, so I did a little research and there it was — Café Terrace, painted in 1888, just one year after Anquetin’s work. A little more digging showed that the two artists were friends in Paris and that Anquetin’s style was adopted briefly by van Gogh during his time in Arles.

This painting hangs in the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut.

KEEPING TIME

Why Music and the Clock are Forever Intertwined

Text by Paul L. Underwood

“And it’s time, time, time that you love,” warbles Tom Waits on the chorus of his 1985 ballad dubbed, suitably enough, “Time.” “And it’s time… time… time…” The wistful sentiment hits hard, nestled between verses about a typically Waitsian tableau of orphans, “shadow boys,” and a weeping Napoleon in a carnival saloon. Taken together, the effect is like hearing a man stalling, painting verbal portraits to distract himself from the reality that time is all we have, and it can’t be replaced, and it’s running out whether we like it or not.

Music and time are intimately intertwined. We admire a drummer’s ability to keep time. We speak of tempos, of rhythm, of speed (which, after all, is defined as distance over time, and music has a way of bridging distances). It’s appropriate that Prince, perhaps the master of manipulating time in a pop song, whether stretching out a slow jam or stopping on the right beat during a dance routine, expanding a note in a guitar solo or fluttering through a flurry of them, put together a group and called it The Time. We know about how long an ideal pop song should be: Two or three minutes, enough to convey the mysteries of the universe, at least in Bruce Springsteen’s telling — after all, we learned more from a three-minute record, baby, than we ever learned in school, at least according to “No Surrender.”

It’s no coincidence that on the back of your favorite record, you’ll probably see a list of the tracks, followed by how long each one of them is. In the analog days, this could give a record an air of mystery. What could Bob Dylan have to say in the Time Out of Mind closer, “Highlands,” and why did it take fully 16 minutes to say it? (Dylan has long pushed the temporal limits of pop music, having ascended to the summit of the charts in 1965 with “Like a Rolling Stone,” whose six-minutes-and-change notoriously couldn’t be contained on one side of a 45.)

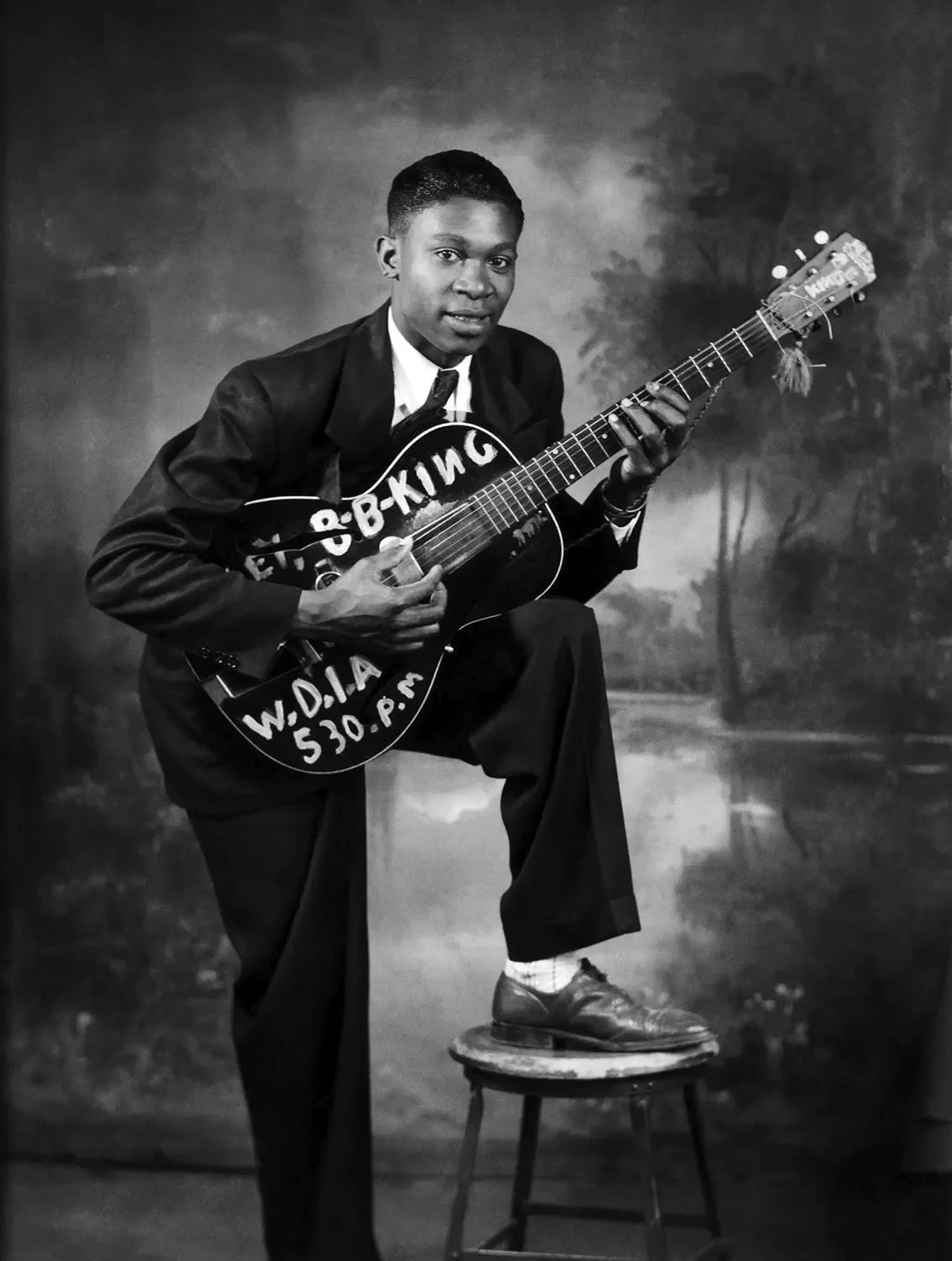

We measure dance songs in beats per minute; we awe at jam bands’ ability to improvise and noodle for a half-hour or more; we settle in for hours at the opera, with Wagner’s epic Ring Cycle requiring 15 wrenching hours or more for a complete performance. (To sit through a complete performance, let alone to perform it, is worthy of the medals they give to marathoners at the end of the race.) A single note held just so can offer transcendence, as anyone who has listened to B.B. King can attest. But sometimes the whoosh of performance, the cumulative energy that climaxes with, say, an encore where Bono belts “Where the Streets Have No Name” or Keith Richards skronks his way through an encore of “Satisfaction,” could not be duplicated without the long, steady buildup.

Every year, our streaming services will inform us just how many hours we spend listening to music on their services. These can seem Herculean — days upon days spent with aural stimulus, even if it’s just the background stuff that “Focus Flow” playlists are made of. I recently saw that the aforementioned Mr. Dylan has performed “Like a Rolling Stone” more than 2,000 times — given its length, that amounts to nine full days of his life, playing the same song. How many days have I spent listening to my favorite albums? Or, if you’ve worked in a store or office where the music was not of your choosing, how many days have you spent listening to your least favorite songs? (By my best estimate, I heard the Goo Goo Dolls’ “Iris” at least 1,000 times in its late-’90s heyday, without intentionally listening to it once. This translates to nearly 67 hours, almost three full days of my life … so far.)

Malcolm Gladwell famously asserted that it takes 10,000 hours of practice to master something, and he used the Beatles’ pre-fame Hamburg period as an example. The Fab Four arrived in Germany as an eager and talented garage band and left as masters of their craft, including leveraging their off-the-charts charisma. Those who have done the same might not replicate the Beatles’ generational success, but to spend your precious hours in their presence for a musical performance is to be a witness to the limitless nature of human ingenuity, to bask in the miracle of their devotion, which expertly determines when and how to make their instruments vibrate (and when not to), sending sound waves into your ears and on to your heart and soul.

Then again, maybe not. Perhaps the most well-known duration in music belongs to a composition by avant-gardist John Cage. The piece, “4’33,” demands that the performer sit at the piano, ready to play, and then do nothing — leaving the audience to experience the title’s time period in silence.

THE VALUABLE TIME OF MATURITY

by Mário de Andrade:

Poet, novelist, essayist and musicologist. One of the founders of Brazilian modernism.

I counted my years and realized that I have less time to live by than I have lived so far.

I have more past than future.

I feel like that boy who got a bowl of cherries. At first, he gobbled them, but when he realized there were only a few left, he began to taste them intensely.

I no longer have time to deal with mediocrity.

I do not want to be in meetings where flamed egos parade.

I am bothered by the envious, who seek to discredit the most able, to usurp their places, coveting their seats, talent, achievements, and luck.

I do not have time for endless conversations, useless to discuss the lives of others who are not part of mine.

I no longer have the time to manage sensitivities of people who, despite their chronological age, are immature.

I hate to confront those that struggle for power, those that ‘do not debate content, just the labels.'

My time has become scarce to debate labels, I want the essence.

My soul is in a hurry. . .

Not many cherries in my bowl,

I want to live close to human people, very human, who laugh at their own stumbles, and away from those turned smug and overconfident with their triumphs, away from those filled with self-importance.

The essential is what makes life worthwhile. And for me, the essentials are enough!

Yes, I’m in a hurry. I’m in a hurry to live with the intensity that only maturity can give.

I do not intend to waste any of the remaining cherries.

I am sure they will be exquisite, much more than those eaten so far. My goal is to reach the end satisfied and at peace with my loved ones and my conscience.

As per Confucius “We have two lives, and the second begins when you realize you only have one.”

MAKING THE MOST OF 4,000 WEEKS

Text by Carlisle Sego

Join me in an exercise: Without doing any mental math, guess how many weeks make up the average person’s life—follow your gut and write down a number.

Got it? Great. Brace yourself.

4,000 weeks—that’s how long the average human is of this world.

If you played by the rules, you probably guessed a number in the tens of thousands. My guess? 30,000 weeks. Nearly everyone overestimates, and confronting the minuscule actuality of 4,000 short weeks to achieve all that we aspire feels akin to taking a bucket of cold water in the face.

While this exercise may initially feel grim, Oliver Burkeman guides his readers down a path to liberation that can only be achieved by facing our finitude in his New York Times bestseller, 4,000 Weeks.

I was allured by the book’s clever tagline: Time Management for Mortals. As a highly motivated individual and a textbook Enneagram 3—“the achiever”—I place a great deal of importance on my work and have always been captivated by tools and ideas promising increased productivity. I strive for excellence, often to a fault, which I know sounds like the kind of humble brag you pull out of your back pocket when asked about your weaknesses in a job interview—but here’s why it’s not: I have allowed the highs and lows of my career to bleed into my personal life more often than I should. I often subconsciously decide whether it’s been a “good” or “bad” day based on how many items remain on my task list.

Burkeman’s 4,000 Weeks was the soul salve I didn’t know I needed. When this lemon-yellow book arrived on my doorstep, I sat down, pen in hand, to begin what I assumed was yet another productivity book that would eventually gather dust on our bookshelf with margins full of notes I would never revisit. But, chapter after chapter, the contents of its pages continued to surprise me. Burkeman’s tone is gentle, his words reflective, and his imagery clever. He makes countless references to philosophers and great thinkers throughout history as he implores his readers to adopt a new perspective: Rather than thinking of time as a resource to be used and optimized, think of time as a spectrum in which life takes place. When we stop “planning” our lives to achieve as much as possible within a set amount of time and start acknowledging the radical truth that we exist within time, we relinquish a false sense of control and can begin to live more fully in this moment.

“The day will never arrive when you finally have everything under control—when the flood of emails has been contained; when your to-do lists have stopped getting longer; when you’re meeting all your obligations at work and in your home life; when nobody’s angry with you for missing a deadline or dropping the ball; and when the fully optimized person you’ve become can turn, at long last, to the things life is really supposed to be about. Let’s start by admitting defeat: none of this is ever going to happen.

But you know what? That’s excellent news.”

This simple sentiment resonated deeply with me, as I imagine it also will for many of you. I read this book at a pivotal time in my life and career, just before my 28th birthday (1,451 weeks, to be precise). I had spent much of the last half-decade burning myself out and living mentally in the future as I doggedly pursued an unattainable state in which I had reached all of my goals, was ahead of schedule, and could finally slow down to be present. As I devoured this work, I found the clarity to understand that this was a delusion—an impossibility perpetuated by a society that prioritizes output overall.

In confronting this truth and reframing my concept of time, I felt a weight lift from my shoulders. I began challenging myself to set boundaries on my workday and to sit in the discomfort of closing my laptop instead of crossing one more thing off my to-do list. I began to reflect on the kind of life I wanted to live and to direct my energy toward things that aligned with my values. I began placing the relationships and experiences I truly care about in the forefront of my focus for the first time in years, and I felt my life becoming more vibrant and fulfilling as a result of this practice.

When my husband arrives home after a long day, I flag the email rather than finishing my response, set my phone face-down, and fully engage in conversation with the love of my life. I notice how handsome he looks and ask questions that paint a picture of what his day looked like.

I follow cues from my body that had previously gone unnoticed. I trade my laptop screen for a hot bath when my eyes need a break. When my brain craves endorphins, I go on a spontaneous run or blast Charli XCX and close the curtains to dance with our dogs. I reach out when my heart longs to catch up with my friends or hear my mom’s voice.

Today, I am more present in recognizing novelty and joy in the smallest, most mundane moments. I notice how the hot, heavy summer air smells like honeysuckles and earth as we walk our dogs after an afternoon shower. I pause to watch the afternoon sun drench our butter-yellow kitchen, and I feel alive. When I lie awake at night thinking about the emails that await in my inbox, I make the conscious decision to instead shift my attention toward reflection.

This book taught me the invaluable lesson of being an active participant in my life—I’m only here for a flash in the grand scheme of time. NOW is my chance to use it well. And while I sometimes fall back into old habits, pulling the blanket over my head and claiming it’s out of “necessity” because that’s how it feels, now I at least understand that by choosing to focus my attention, time, and effort toward the most important areas of my brief existence, I am inherently choosing to miss out on others. And that’s a beautiful choice to face.

TIMELESS TREASURES

How Interior Design and Collections Have Evolved Over Time

Text by Kelsey Ogletree

Developing your home’s interiors from a collector’s perspective doesn’t completely separate you from the world of trends. However, taking this deeply personal approach can help liberate you from the never-ending trend cycle.

Michael Diaz-Griffith, executive director and CEO of the Design Leadership Network and Florence native, passionately believes in this sentiment, so much so that it inspired him to write his book, The New Antiquarians (Monacelli, 2023). The oversized coffee table tome highlights nearly two dozen young connoisseurs and their spirited interiors, photographed in such a way that reflects their livable nature rather than unrealistic perfection.

Collections ranging from rustic stools to portrait miniatures to wooden masks to bronze reliefs decorate the rooms and walls of their homes, encompassing tiny apartments, suburban houses, and grander residences. They’re living, breathing spaces that are never quite “done” but always evolving.

Indeed, everything old is now new again, a reflection of the cyclical nature of design trends. In the ’80s-’90s and into the 2000s, people had a strong interest in formal English furniture and other types of high-style antiques, says Diaz-Griffith.

This tastemaking happened in New York and fairs like The Winter Show before trickling down to middle America, even to Alabama. “It’s the bedroom suite, the Chippendale dining room chairs, the jewel tones,” Diaz-Griffith shares. Because these items were in such high demand, ultimately, we ran through the supply of authentic antiques, and so the reproduction boom began.

The reproduction pieces started to fall out of favor around the same time as the financial crisis when the antiques market also took a dive and the “keeping up with the Joneses” mentality entered the picture. Around 2014-15, the pendulum began to swing back, and pieces that had been deemed unfashionable — like English furniture — came back into the mix. In the past few years, we’ve seen the rise of the Grand Millennial aesthetic. Make it: Everything old is cool again.

“It’s still kind of an unusual choice to be young and say, ‘I’m going to have a fabulous English country house look in my dining room,'" says Diaz-Griffith, "but it’s happening.”

Adrianne Bugg and Brandeis Short, owners and principal designers behind Florence-based interior design firm Pillar & Peacock, founded in 2011, say the ’90s have returned. This look manifests both in fashion and in interiors but in a more sophisticated way.

“Our younger clients are going back to this trend of what we would see in our grandparents’ generation: a more traditional antique look mixed with updated pieces,” says Bugg. She’s seeing color palette throwbacks, too. Think hunter greens, cinnamon spice, maroon, and yellows making a return, mixed in with brighter hues that give it a different feel.

The art of mixing antique and modern is not a new concept. Three decades ago, when Houston-based interior designer Lucinda Loya founded her eponymous design firm, influences from antiquities were everywhere, and blending old and new has continued to be a common theme in interiors. There’s been one big change in recent years, though: cleaner lines.

“We are all busier than ever, and I think that has emphasized that clean lines are important,” Loya says. “Coming home from a hectic day and coming into a chaotic environment of layers and layers of interiors isn’t preferred anymore.” Instead, homeowners want to come home to relaxing spaces that make them feel at peace.

Though Loya specializes in modern design — Architectural Digest called her style “unabashedly bold” — she doesn’t shy away from using antique pieces, particularly unique collections, always with an eye toward clean lines. For instance, in her own home, she displays a collection of French rosaries dating back to the late 1800s on the wall as an art piece rather than in a bowl on a coffee table.

Collections of any kind help to make a space feel warm, cozy, and authentic, Loya says. “If they’re honest artifacts and not just decorative, they’re serving almost as sculptures that you can accessorize with.” She likes to take a client’s collection — whether it’s guitars, record albums, candlesticks, or books — and intentionally create an art installation in a concentrated space, rather than scattering throughout the home where the throughline between pieces can get lost.

Paige Thornton, another interior designer based in Florence, notes that the hunt for antiquities is, increasingly, as much about the personal thrill as it is delivering on her clients’ requests. “We’re seeing a big shift in design where people are wanting soulful pieces in their home [again] that have a story, that almost feel like an old friend that you love and cherish,” she says.

For a recent new project, Thornton ventured into a dusty attic to retrieve family pieces dating back decades. “I had the shakes because I knew I wanted to dig through every single thing and find all the treasures,” she recalls. Among her finds was a gilded chandelier that hadn’t been hung in nearly 100 years. She had it rewired and hung it in her client’s powder room, which added layers of character, design, and history.

As treasured as these antiquities might seem, the modern take from a design perspective is not treating pieces too delicately. Collectors are framing their historic objects in an updated way, incorporating greater sensibility than generations before.

“People need to choose a way of living with objects that work for them, and in terms of the picture-perfect ideal, I think that’s fading,” says Diaz-Griffith. While so many used to seek home inspiration from shelter magazines and design books, living in the age of TikTok has changed the way we consume visuals.

Curated spaces that are a little bit grittier and a little more lived-in are replacing the highly styled and filtered images of the past. “Culture is moving toward something that’s less buttoned up and more real,” says Diaz-Griffith. “I think that’s a healthy thing for everyone, and it’s also affecting the way we look at interiors.” Talk about life imitating art.