Issue 8

Play

theStudio Journal is a product of Florence, Alabama, made by Southern creatives with big ideas about the world. Each issue explores a single, thought-provoking theme through art, photography, and writing. We aim to be radical and relevant. We believe theStudio is a respite from the 24-hour news cycle. We believe in print. We hope that you will hold this issue in your hands, share it, display it, and return to it.

From the Editor: When Robert approached me about editing theStudio, he told me about its inspiration: the groundbreaking Visionaire, an art-driven publication that shattered the definition of “magazine” through its experimental (and experiential) content and presentation. One edition was 7 feet tall. Another paired images with perfume.

Like Visionaire, each issue of theStudio explores a single, thought-provoking theme. We talked about defining its identity without putting up creative barriers. Our goal, we agree, is to create a beautiful magazine and build a community of curious people.

As I assembled a pitch guide to send to Play issue contributors, I thought about the word play and its connotations.

Play music. Play games.

Play with fire. Play with food. Play tricks.

Play dress up. Play the part. Play the fool.

Play to win.

Writers and photographers showed up with stories and images that reflect their voices and reveal deep meaning in unsuspected places, stories that delight and challenge, enlighten and compel reflection. Pieces that are playful with purpose: a guiding principle not only for this issue but for theStudio itself. –Alison Lyn Miller

From the Creative Director: After every issue (we are on our eighth one), I ask myself why I do this. And then I get comments like I learned so much about beauty from your last issue or I never thought about sounds like that until I read the magazine. Comments like the contributors page is my favorite part, and I have read the magazine from cover to cover three times. They make me stop and think.

But after our last issue I didn’t think I had the energy or time to devote to it. I reached out to creatives I admire. Natalie Chanin and Billy Reid, whom I have worked with for more than 20 years, whom I respect immensely for their talent, work ethic, and dedication to their craft. John Paul White, whom I have photographed over the years with his band, the Civil Wars, and whose music feeds the soul. Angie Mosier, who started off as a stylist/writer and is now an amazing photographer, introduced me to the equally insightful and talented John T. Edge. John T. led me to Alison Lyn Miller. Our creative cooperative was born.

I love the intimacy of holding printed paper in my hand, studying a photograph, and reading something on the printed page. These things inspire me more than scrolling through Instagram. Each one of our cooperative collaborators doesn’t have the time for this, but they have somehow made it. I’m honored they see value in printed matter, as I do. –Robert Rausch

STATE OF PLAY

By Natalie Chanin

Photography and designs by Gabriela Batista. From Proud South Craft by Lidewij Edelkoort. Publisher: Lecturis, 2025.

“The true object of all human life is play.” —G. K. Chesterton

Play is often thought of as the opposite of work. Yet for the designer, the artist, the maker—for me—it is the beginning of everything. Play is where we begin as children; it’s where design becomes experimentation, and where the everyday object becomes something alive.

Play is where imagination begins but regeneration is where it continues. To play is to ask what if? To regenerate is to ask what next?

Our work as makers, artists, and designers is never static. Every object—every handprint in clay, wood, fabric, or food—carries the potential for renewal: of self, of community, of the systems we touch. Regeneration is what happens when making becomes cyclical, when what we create not only sustains but restores.

Take the spoon. Simple, universal, unassuming—and infinitely full of possibility. It’s often the first implement we learn to use. Before the spoon, we eat with our fingers; with it, we learn intention, balance, and care. That small act—bringing nourishment to ourselves—might be the earliest form of design interaction we know.

But one spoon joined with another plays music. We use them to dig in sandboxes, measure ingredients, scoop ice cream, and serve love. This object, so common in our lives, even describes how we might nurture a loved one through spooning. The spoon, in all its forms, embodies regeneration—an object created from the natural world that returns, again and again, to sustain and connect.

The book Proud South Craft lies on my design table at home. It’s open to Chapter 14: Proud Spoons & Fetishes, which presents the work of Brazilian artist Gabriela Batista. Across eight pages, her handmade spoons unfold like a study in rebirth. Each is carved from wood, polished by touch, and imbued with color, foraged materials, and pattern—and, I would argue, story, joy, and delight. Some are ceremonial, others playful—each one a transformation of raw material into something that carries both spirit and utility. They are, quite literally, design as regeneration: matter renewed through human imagination.

Regeneration speaks not only of materials and sustainability but also of memory, lineage, and community. My work—and the work of Project Threadways—has always lived at the intersection of art, humanities, labor, education, and community. I am drawn to the cycles that connect raw materials to objects, hands to labor, past to future, material culture to life, life to delight. Every material, every life, tells a story of transformation: cotton grown in Southern fields, spun and sewn by human hands, reimagined through new generations of labor and play.

Regeneration is the playground for designing new systems. It reminds us that design must restore as much as it consumes. Whether through fiber, fabric, or form, we have the opportunity—and responsibility—to create processes that delight, inspire, and give back more than they take—the power to design community.

When I think of regeneration, I think of hands: the artisans who sew, the farmers who plant, the teachers who pass knowledge forward, the designers who imagine new futures from old traditions. I think of how an idea, once sparked, can travel across disciplines—through food, craft, storytelling, and scholarship—to renew our collective sense of belonging.

The spoon, humble as it is, becomes our metaphor—a small act of renewal made tangible. Every time we lift it, we participate in a lineage of nourishment; we play in the sandbox and connect with a design that stretches back millennia. Its shape is ancient, but its meaning is alive: proof that regeneration often begins with simple tools, the spirit of play, and human hands.

Good design, like regeneration, lives in dialogue: between maker and material, tradition and innovation, the seen and the unseen. The spoon—the work—cannot escape its purpose; it holds, it carries, it sustains. Within that purpose lies infinite potential to create delight, to embody care, to give form to renewal.

If play begins the story of design, regeneration ensures it continues. It is what happens when imagination turns into responsibility, when we make not just for today but for tomorrow.

Play is the courage to ask what if—and to follow where that question leads. To ask, what next.

Play is the spoon in the hand—the humble tool that becomes extraordinary through imagination, curiosity, love, and the desire to regenerate stories.

Because play is how we begin again. It’s how we learn, repair, and reimagine. It’s how the hand rediscovers the joy of making—and how play, in turn, restores the world.

ON THE BUTTON

A history of the iconic Play triangle

By Paul L. Underwood

One symptom of a well-designed object is that we fail to notice it. Another is when it outlives its original reference to take on a life of its own. (Think, for example, of how you save a file by tapping a floppy disk icon, even though most people under 35 have never seen, let alone used, a floppy disk.) Still another is when no one is quite sure where it came from. Success might have many fathers, but something as humble and pervasive as the triangle that symbolizes “Play”—what one designer calls “possibly the most ubiquitous modern technology symbol there is”—appears to be an orphan.

So where did it come from?

Well, in ye olden times, there was no need for a play button at all. To hear music, you simply dropped a needle on a record or tuned into your favorite radio station. Or, even earlier, you played the music yourself, on an instrument. But the advent of magnetic media, such as reel-to-reel tapes and cassettes, necessitated some sort of control to indicate how to start the dang thing. Early versions used the word itself, “Play,” but that had the considerable drawback of requiring translation for different languages and markets.

Enter the triangle.

“Unfortunately, neither the right-pointing triangle nor the double pause bars seem to have a definitive origin,” writes Gizmodo’s Bryan Gardiner. “The direction of the play arrow indicated the direction the tape would move. Easy.” For sound engineers working in high-stress, often loud environments, the use of a big, bold triangle offered clarity, a simple way to communicate how to start listening to the recording. Which of those early sound engineers selected play, however, is lost to history. (Some have suggested a Swedish engineer, Philip Olsson, created it while working in Japan, but this anecdote seems to have originated online, with sources essentially citing one another in a circle worthy of another omnipresent button, record.)

Of course, the triangle has friends: The square (stop), the double-triangle (fast-forward or reverse), and the double-bar symbol for pause, which Gardiner notes resembles the caesura in musical notation, two diagonal lines that tell the player to wait a beat. (Others have pointed out that it resembles the physical bars used to stop or pause a tape.)

Over more than a half century, these symbols have played a supporting role in famous product designs from Braun, Phillips, Sony, Apple, and more. You can still find early Grundig reel-to-reel machines on eBay, and they look like something from a Bond villain’s lair. Ditto those from Braun, whose Dieter Rams is probably the best known industrial designer of all time. “The symbolism was acoustic as well as visual: every time the “record” or “play” button was pushed, a magnet set the lever into operation with an audible click,” according to a description of one of those reel-to-reels in the 2009 catalog, BRAUN—Fifty Years of Design and Innovation. “The linear arrangement of the control buttons hearkens back to the repertoire of earlier audio appliances, as does the plexiglas cover—an unusual feature for a tape recorder.” In other words, even in the ’60s, there was something intrinsically familiar about the play button and its companions, at least in well-designed products.

The play button was adopted by the masses in the ’70s, with portable cassette players from Philips and Panasonic. But the button’s big moment might have come in 1979, when Sony introduced the Walkman, the first cassette player meant to be carried around with you, a lightweight and oddly beautiful device that foreshadowed a world where everyone carries a library of music in their pocket. Naturally, the play button was central to the device, sometimes denoted with a green button, and often accompanied by the word “Play.”

About a quarter-century later, the first iPods combined pause and play into one button with two symbols, confusing at least one user*, and preserving a tactile click, even though it wasn’t strictly necessary. Moreover, the word “play” wasn’t on the device at all—by then, it was universally understood what the triangle met. In the years since, the button has become the centerpiece of the YouTube logo, and—unsurprisingly, given the button also appeared on VCRs and DVD players—is often seen online over playable social media videos.

Today, actually pressing a play button has largely given way to the less-satisfying sensation of tapping or clicking a screen. But online or off, the humble triangle has sticking power.

*Me. The user was me.

STAGE RIGHT

By John Paul White

Sometimes, the last thing I want to do is play.

I must play. It’s lifeblood. I can’t imagine a world where I didn’t have music to express my deepest thoughts and fears, to explain my wants and needs, to satirize, entertain, protest, and promote change.

I’ve spent so much of my life scratching and clawing my way to an existence where I can play for a living—and pay my bills. If I’m keeping my family’s heads above water, my business is thriving. Each year, it gets tougher. The pie gets smaller, costs increase. I get older, more cynical. I long for my bed. For my wife and kids. For “normalcy” and “structure.”

And we don’t spend a lot of time actually “playing” in my world. Musicians like to joke that “we play for free—we get paid for all the other shit.” There are so many other obligations that come with it. Social media, promo, marketing, strategizing, budgeting. Insane amounts of travel. Media. Radio interviews. And clothes (thank you, Billy). My friend said, “I love that you have a job in which you could wear anything you want—and you choose to wear a suit.” It’s my uniform. It’s the transformation apparatus that allows me to step into a role, or another personality, or whatever it is that happens when you’re on stage. But I must have multiple suits. And they must be clean. And I must make sure I haven’t ripped the crotch out of them.

I’m a fortunate human being, and I recognize that. I don’t take for granted that I have a job lots of people want. I worked incredibly hard to make this my livelihood. My family made many sacrifices. I feel guilty sometimes. There are a lot of people out there who are more talented than me and have worked just as hard, but have never gotten the opportunities I’ve had. But sometimes I want to trade with them. Have a routine, insurance, and a pension…

This life takes a toll. I spend each night purging demons and sharing secrets. And then I do it again the next night before the wounds can even heal. It’s an unhealthy vocation at best.

But oh, when it’s right.

When the room is full of people and we’re all tethered in a way where we feel each other’s emotions, there’s no greater “job” on earth. Seeing someone process a lyric or melody and visibly change in real time. The moments when I’m able to articulate things others can’t or won’t say, and the thank-yous after the show. When the monitor mix is perfect and you don’t have to strain to hear yourself. When years of practice allow you to navigate improvisational changes on stage and create something that never existed before and never will again. These are the highs we chase on stage and in every other part of our lives. These moments carry us, buoy us, heal us. Remind us that it’s all worth the cost. Remind us why we’re here.

To play.

PLAYING NORA

Becoming Myself by Cosplaying the Girl That Saw Me

Words by Amy Pedulla + Photography by Will Crooks

Let her talk about the band, I think. She won’t notice that I don’t know who they are if I nod.

Nora talks about the band. Nora knows about this band, but she also knows about three other bands, too. Have I listened to the latest record she mentioned to me last week? The name of which she wrote down on a notecard so I wouldn’t forget? Of course, I haven’t, but I murmur something that sounds like a muffled affirmation. Nora talks about the concert venue where this band, Stars, is playing, how hard it was to get the tickets, how much she spent on them, and which of her friends in the 10th grade want to go with her.

I’m a freshman in high school and Nora has hand-selected me, plucked me from hundreds of sleepy teenagers sliding through the hallways, and crowned me the winner. I don’t know why Nora has bestowed upon me this honor.

“Hey, you!” I think she called out once in a crowded hallway. I had never met Nora then, but Nora knew me. Nora knew everyone, knew who was in which friend group or on the edges of it, who hung out where. But Nora chose me. She didn’t mind that I had no idea who this band was; she just wanted me to tag along. She saw something in me I hadn’t been able to see in myself yet.

She possessed an uncanny ability to scan and locate specific women in a crowd and decide to know them. She dispensed without any preamble, jumped right in. Her respect came in the form of a run-on sentence: you were along for her ride, whether you wanted to be or not.

Nora wore blue Saucony sneakers back then, shoes I now still wear; I must be on my third pair, at almost 35. There she is again, I smile to myself, and let the subway doors close behind me.

I played the part of Nora in other ways as I got to know her. She called me up one day out of the blue, mere weeks before she went off to college. Might I want to take over the sports column she wrote for a town newspaper? It was the second time she had chosen me in ways I wasn’t conscious enough yet to understand would concretely shape the direction of my life.

There is something about Nora’s mental velocity I still parrot. Even now, I see her influence in the way I interact with other women I admire. The way I talk about what book I’m reading with a group of friends, often oblivious to a tendency I have to launch right into what I hated about the book before checking to see if anyone else had heard of it, let alone read it.

After I went off to college, left college, and moved a bunch of times, we lost touch. Not out of notable drama, just natural drift. But a year ago, I decided to learn how to play guitar. It was a project I had put off for years; it always slipped to the bottom of a priority list packed with other things, interrupted by various life stages, disappointments, and busy periods of growth. I noticed more grays in my bangs in the mirror, found a teacher, and finally, definitely, booked a class.

My teacher asked me what songs I wanted to learn how to play. I could barely tune the guitar on my own yet, but I called up a most-played list on YouTube from my phone and wondered which to tackle. I smiled, sitting in Maya’s apartment on her couch, when the song “Set Yourself on Fire” by Stars winked at me from the screen. A song by the band I had seen with Nora at that concert all those years ago.

I notice her fingerprint in other ways. The urgency with which I text a new friend that I’ve purchased tickets to a show. I trust they will be flattered that I’m confident they would enjoy the music too. I intuit, the way Nora once did with me, that this specific friend I’ve selected will enjoy a spontaneous evening with me.

And I wonder if my new friend thinks, I’ll let her just talk about the band.

PLAY FIGHTING FOR GOOD

Words by Alison Lyn Miller + Photographs by Adam Smith

I turned seven in 1990, the year The Ultimate Warrior took the belt from Hulk Hogan at WrestleMania VI. Professional wrestling permeated popular culture, but I grew up and rested it next to the other relics of my childhood: Micro Machines, Michael Jordan, New Kids on the Block.

Then one February night in 2019 I showed up, out of curiosity, to a wrestling show in Athens, Georgia, where I live, and surveyed a thrilling, unfamiliar scene. The cement floor around the ring disappeared beneath the mass of spectators, and I wiggled through the bodies to get a better view. In the ring, a guy in neon-green tights and calf-high white boots slammed his opponent to the mat with a concussive boom.

Next to me, a man with the giddy face of a dad at a dance recital held up his phone to take pictures. “Do you know that guy?” I asked, pointing to the ring. He turned his head. “That’s my cousin!” he yelled, and told me that Axel, now pinballing between the ropes, worked as a mailman. Slack-jawed, I returned my gaze to the ring.

The symbiosis between performer and spectator stretched like a high-voltage powerline. Fans flinched with the punches and then reared up with a mix of insults and encouragement, lobbed at maximum volume. The wrestlers heeded the call. When they were down, they waited for the fans to rally before laboring to their feet. Soon I was yelling a name I’d never heard with a force I barely recognized.

I wanted to know everything. Who were the people sitting around the ring? Who was the guy in knee pads and Speedo-like trunks peeking from around the corner? What compelled them to be here, play-fighting in front of a beer-drunk crowd at 10 o’clock at night?

In the years that followed I asked these questions in a backyard ring and warehouse training center, in locker rooms before shows, in living rooms, coffee shops, and gyms. I sat in the passenger seat of Axel’s car as he delivered DoorDash orders and learned that he actually used to sort U.S. Mail packages on third shift at the Atlanta airport.

Nothing is more primal than wrestling’s playful violence. Watch toddlers roughhouse each other without injury, or dogs taunt and tackle one another, then walk home, leashed, satisfied, and better for it. We’re taught to control our feelings, to walk away without making a scene. Around the ring we let loose. The quiet acknowledgment that everyone walks away unharmed grants fans license to celebrate violence, and it feels good.

Play fighting into adulthood is adrenaline-fueled social play that reinforces boundaries and releases dopamine. The act of violent role-playing night after night buffs out the hurt and hate and breeds community. Late one night I sat around a table at Chili’s with wrestlers after their show as they tore into pork ribs and fried pickles. Another time, on Christmas night, I communed with a sold-out crowd at a bruised-up former school gymnasium and listened to the boy next to me name the moves he saw in the ring—“Reverse suicide dive!” “Piledriver!” “Big belly-to-belly suplex off the top”—and their provenance like a sommelier sniffing out terroir.

Our tendency to imbue characters with meaning and relish in stories—fact, fiction, or somewhere in between—is part of what makes us human. Playing a role in the ring allows us to be something greater than the sum of our real-life roles and duties. There’s danger in making up stories and exaggerating details to manipulate people’s emotions, to be sure, but consider its possibility for good. If on Saturday nights you show a small crowd you’re the greatest of all time, do you eventually become it? Or at least feel like it? And isn’t that what matters?

“Being out there makes me feel like I’m a star bigger than what I am outside of wrestling,” a performer named Chop Top, in rural north Georgia, told me. “Some people just know me as the guy always outside working on his truck. I have this fire that’s built in me when I come out there.”

In a world where truth feels more and more elusive, wrestling offers a promise, a mutual understating between performer and spectator: The action in the ring is real, but it’s not as bad as it looks.

Wrestling’s hyperbolic faceoffs resonate with kids, who learn balance and coordination, as well as both verbal and nonverbal communication, through play fighting. Then and now, they recognize the televised roughhousing and mimic it on their living room floors. No one gets seriously hurt, they know, because their favorite wrestlers keep reappearing, show after show. Kids learn not to take it too far.

And yet wrestling’s depth has long been overshadowed by its goofiness. It balances on the tightrope between sport and theater: not quite one, not quite the other, easier to dismiss than to acknowledge. It’s garish. It’s loud. Obvious rather than avant-garde.

In other words, it’s a lot like the Dolly Parton of yore, before the intelligentsia recognized her as a beacon of equanimity: unabashed, larger than life, and easy to pick on. And if we allow it, lovable and unifying. A treasure.

Adapted from Rough House: A Father, A Son, and the Pursuit of Pro Wrestling Glory. Copyright © 2026 by Alison Lyn Miller. Used with permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

WORD PLAY

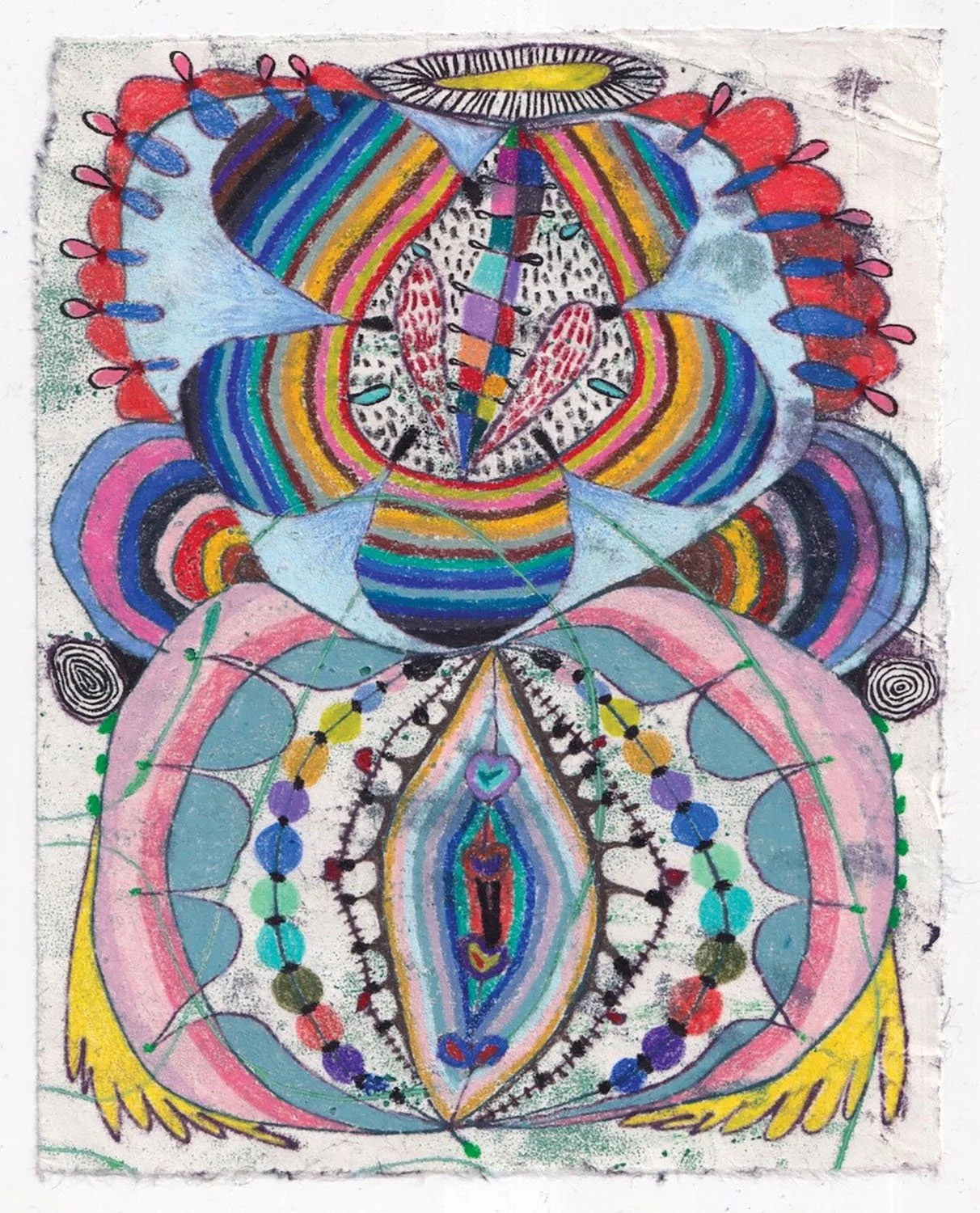

Words by Blair Hobbs + Art by Claire Downes Whitehurst

I’d probably be a lot smarter if my schoolteachers had not defined work and play as opposites. In art class, I got to play with paints and crayons for one hour a week. The rest of my school life was work, and that work gave me stomachaches and sweaty palms.

The apex of my schoolwork misery came in seventh grade. When my prealgebra teacher, Mr. Belk, unknowingly issued me a filthy textbook with a warped cover, I was too nervous to ask for another one. I struggled with elementary math, but this junior-high stuff was extra challenging—not only because numbers turned into letters but also because this new math, in an old book, was preserved by a former student’s amber vomit.

Some of my classmates excelled in these courses and went on to improve the pedagogy. One of those childhood friends, Mary Dansak, became a brilliant middle-school science teacher. One year, as Christmas break approached, she assigned each student a virus to research, draw, color, and cut out like a paper doll. At the end of their presentations, the students—full of knowledge about handwashing and what makes them puke (there’s a theme here)—looped yarn through their glittery viruses and decorated the class tree.

Who knows? If my science and math teachers had combined work with play like Mary, maybe I’d be a retired doctor rather than a retired creative writing teacher. But when I took a poetry class in college, I realized how much prosody resembled puzzle solving—how much it resembled play.

I often play The New York Times’ Wordle game to keep my brain spry. Last Sunday, I got lucky and solved the puzzle on the second guess. Those who play know that while a chance win like this satisfies, it’s also a bit of a letdown, a challenge cut too short. It’s been a long time since I wrote a poem, but that Sunday afternoon, longing for a challenge my lucky puzzle failed to deliver, I went for it. For years, I pondered writing about my near-death experience that followed the birth of our son, Jesse. When my blood pressure plummeted and I passed out, I found myself dreamily walking through the woods to a midsummer cocktail party. My light at the end of the tunnel was full of sunlit people wearing white linen and sipping gin and tonics. I was dying to get to that party until my husband screamed me back to consciousness.

That vision, still brilliantly clear to me 24 years later, became a writing challenge. I coached myself as I used to teach my students. I threw words on the page and then revised. (Purging words is fun, like playing language Jenga. Sometimes revision can tumble down an effort, but it’s the only way to hone words into a poem.) l added figurative language by inserting puns (May day), metaphors (honeysuckle flutes), alliteration (crystal, crown), rhyme (crown and gown), similes (like wind chimes, like ice in crystal glasses), and imagery through specific language (don’t write bug, dammit, write lacewing or orb-weaver!).

William Wordsworth’s romantic verse rang in my ear, guiding content and an oh-so lofty tone. And while it’s cliché to experience a light at the end of a tunnel, I was proud my subconscious declared that a cocktail party promised to be beyond heavenly; it promised to be heaven. A scene that closely matched my memory emerged from my word pile.

My husband, John T. Edge, and I have little working studios in our backyard, which functions more like a courtyard with a messy mix of hostas, rudbeckias, ferns, sedums, azaleas, peonies, swamp roses, and snowball trees. Café lights twinkle above the fussy fountain. A cement cow and an earless hog graze beneath a leggy lantana.

As I tinkered my poem on that rare writing Sunday, it was tough to not to get rid of the orb-weaver’s dress. While I was afraid “orb-weaver” might sound like a modifier for an audience of Druids, I liked the idea of a dress woven by black and yellow arachnids. I also just like giant spiders.

One morning before I entered my studio, I spotted a lady spider busy spinning her web. It dawned on me that If I had to choose a mascot or a coat of (eight!) arms for our little backyard camp, it might just be the orb-weaver. After all, that smart arachnid, who bullseyes her huge webs with cursive-like stabilimentum, is nicknamed a “writing spider.” And while she writes she spins visual art laced and anchored by redbud limbs and sparkled with sunrise dew. I paused to watch, and when the breeze gently swayed the web, I swore I could hear that crafty spider’s glee.

Labor and Delivery

Of course, It was a tunnel.

It was also a path beneath a dogwood

canopy’s dappled leaf

shadows. Sunlight, up a hill, pulled me

toward the prettiest cliché—

a white-linen party on a May day—

and voices called softly, like wind

chimes, like ice

in crystal glasses. I wore

a baby’s breath crown and an orb-weaver’s

gown. I stepped past lacewings

as they sipped honeysuckle flutes.

Was it a branch

or a hand that crossed my cheek

to summon gravity’s

return? A signal for heaven’s

strange happy hour to recede? I woke

to a shout, my love’s last call,

and watched the angels

turn their backs

and fold my wings away

for a later engagement.

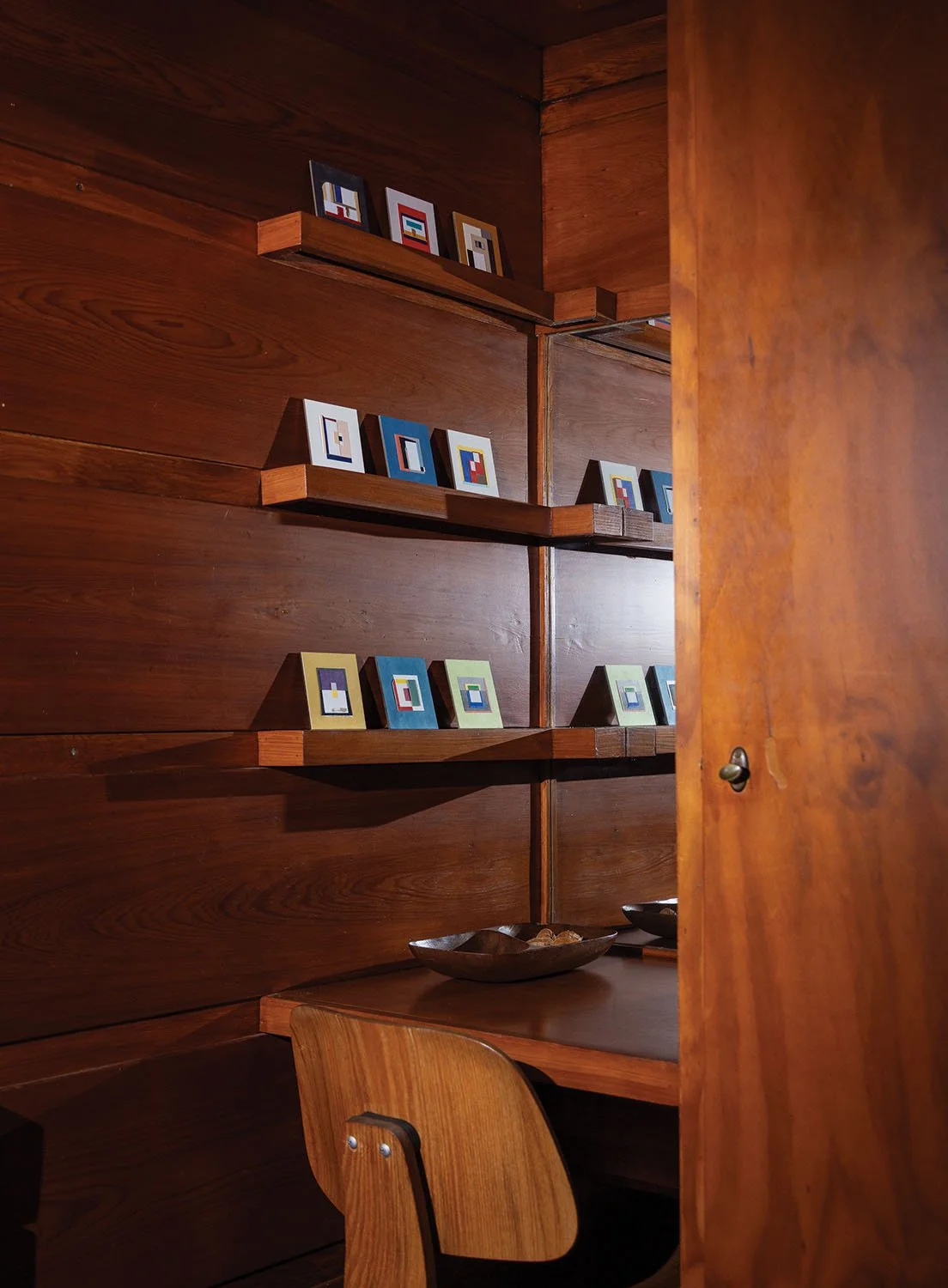

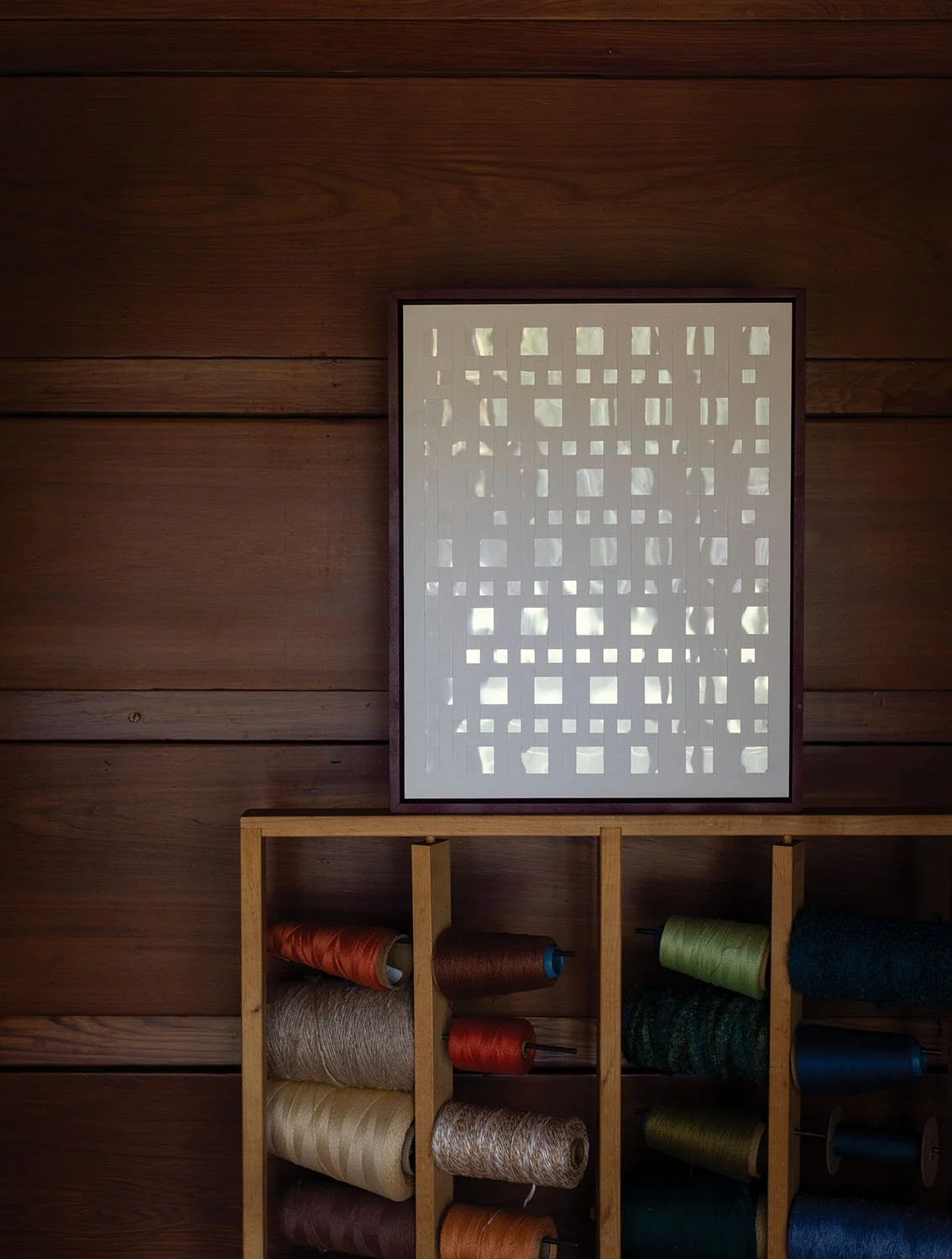

THE WORK OF PLAY

Words by Erin Dailey + Photography by Abraham Rowe

When my son was born, I chose to step away from my job and stay home with him. Six months later, the pandemic began. I was grateful for my decision, but it was still a huge shift. I had always been creative, academically driven, and professionally focused, and motherhood changed a lot. I went through a season of feeling a little lost—not just in who I was, but in who I was creatively.

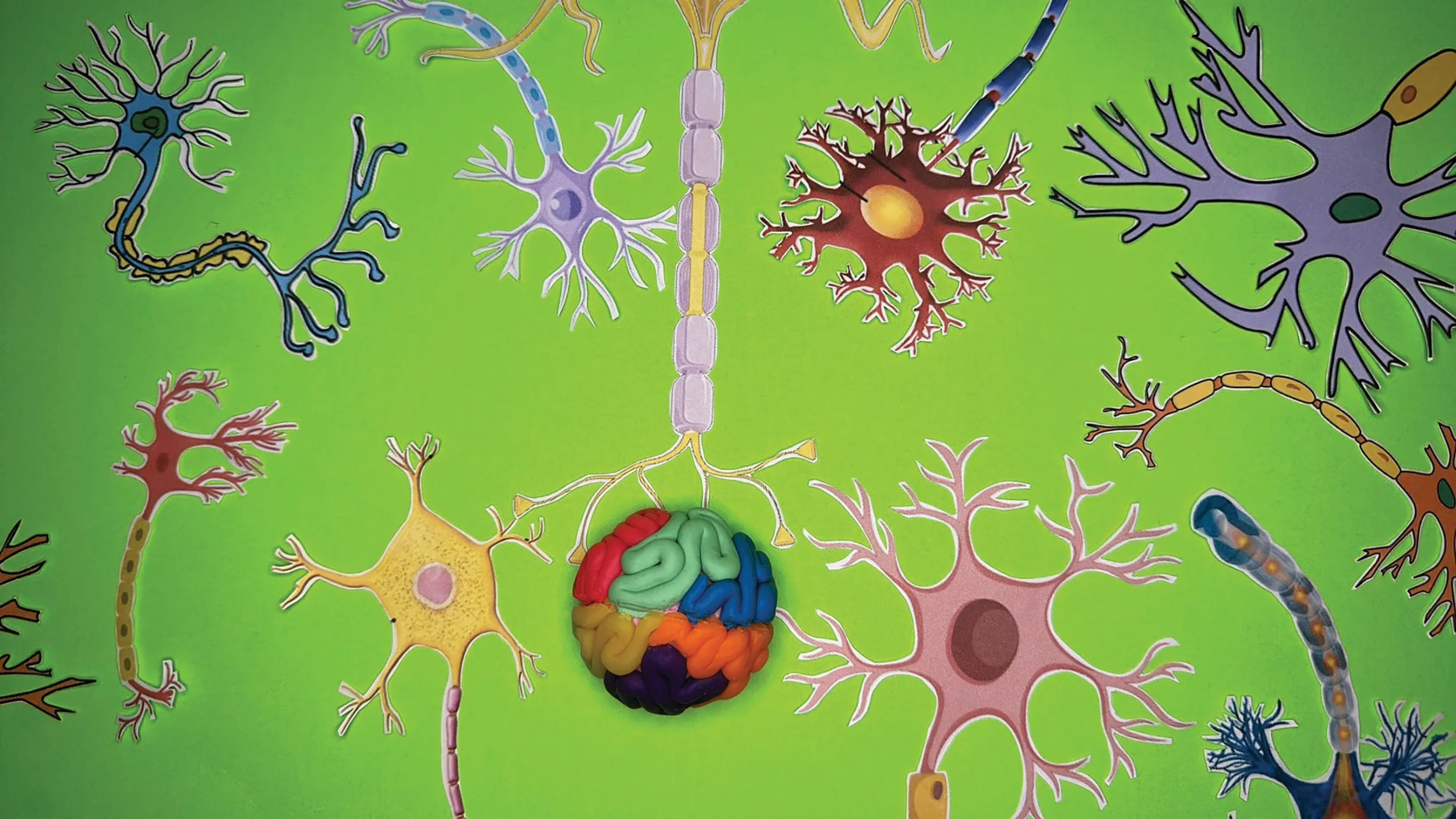

In the summer of 2022, I listened to a design podcast about the history of kindergarten and learned about Friedrich Froebel, the German educator who invented it in the 1850s. Along with his philosophies, Froebel created a series of simple play objects—spheres, cubes, cylinders, wooden blocks—meant to teach young children about the world by exploring forms, spatial relationships, symbolic thinking, and geometry. He called them “gifts” because he believed they helped draw out the natural gifts of a child.

I learned that Froebel’s gifts influenced many 20th-century artists and architects: Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, Paul Klee, and Wassily Kandinsky, to name a few. That connection between early childhood play and modernist design was profound to me, both as a creative person and the mother of a then three-year-old. It brought together so many parts of my life—my early explorations in abstract art, my years in architecture school, my love for design, and my role as a mother. That moment became a catalyst for me, and since then, I’ve felt viscerally inspired to grow as an artist and creator.

Even before learning about Froebel, I was choosing toys for my son that were colorful, tactile, and made from natural materials. They blended beauty and function. He would build trucks and vehicles, abstracted by the blocks and toys he chose to construct them. If you have a child in your life, you likely hear, “Will you play with me?” So I would—and still do—sit on the playmat and play with him and alongside him. I began to see his toys—the colorful Magnatiles and variously shaped blocks—not as children’s things, but as tools for creating art and understanding design with a deep history.

Learning Froebel’s history and making the connection between art, design, and play became my jumping-off point. I started making art, cutting and layering cardstock and bits of packaging from my recycling bin. I played with color and composition. The process reminded me of model-making in architecture school and of Froebel’s gifts—the same simple forms that had inspired so many before me. It marked the beginning of my artistic journey.

Most of us don’t play with children’s toys as adults, but when we do—when we follow a child into that space—we enter an abstract, imaginary world. A part of the mind that doesn’t get used often. It’s joyful, and it’s also deeply creative. Play is often treated as something light, but I think it’s serious work. It’s where experimentation happens, where risks are taken, and where curiosity leads the way. It’s where that joy sparks. Approaching my art this way has helped me take myself less seriously. It’s a paradox: It matters so much, but if it matters too much, I freeze.

It challenges my perfectionist tendencies. It gives me renewed purpose. It connects me to my son. Staying rooted in play and in fun helps me move forward. Froebel said, “Play is the work of the child.” I think it’s the work of adults, too—especially those of us in creative fields. My son reminds me of that every day.

HOME FIELD

By John T. Edge

Posed beside the bleachers, our Red Sox have just won the county Little League championship. Or maybe it was a playoff game. This is how you celebrate a win, my mother says before she uncorks and shakes the green-black bottle. In a photo taken just after that moment, my teammates on the back row grimace or flinch. One of our coaches laughs. On the front row, beyond the reach of her volley, I smile big, all curls and eyeglasses and buck teeth.

My mother doesn’t show. The picture captures just her hand, that bottle, and a stream of liquid. But I know she’s there. In the big leagues, players douse each other after a key victory, she tells us. After teammates and their parents object, my mother grins and shakes the bottle again.

When I tell stories of my Little League days in Jones County, Georgia, just north of Macon, I often begin with that ~1972 moment. Our team played our best that day. And my mother, alive with the imp of the perverse, made her best play. More recently, as I wrote a memoir, House of Smoke, sequencing childhood moments to make a narrative, I’ve come to see my Little League days in new ways.

Two years before that picture was taken, Jones County public schools desegregated and my parents sent me off to a private school in Macon, set in an old mansion, high on a hill. I never fit in at Stratford Academy, where the fathers practiced law, the mothers drove Cadillacs, and their scions pretended superiority. In a recent conversation with a Little League teammate, Joe Farrar, I tell him that when I enrolled in Stratford, my integrated life ended.

I say this with some embarrassment, as if I'm telling Joe something he doesn’t already know about the trajectory of country boys, united by their roots and divided by their colors. Scanning team portraits for the Orioles and Red Sox, the Cougars and Eagles, though, I recognize that each summer, when Little League season returned, my integrated life began again.

I was nearly a teenager when baseball delivered another truth. My team was packed onto a borrowed church bus on the way home from an out-of-town game when a boy I thought of as a friend called my mother a drunk. He said it without malice, as if everyone else already knew. Until that moment, I didn’t know that the woman who shook that bottle got some of her bravado from that bottle.

When men of my age talk about Little League, we talk about play as if it’s a bright and evanescent thing, infinite in our youth, absent in our present. Thumbing those photos from summer days spent on red clay diamonds, I see again. Behind that play, on the other side of those smiles, hard truths lurk, and so does the promise of nostalgia to sand down rough edges and burnish memories.

NEXT PLAY

By Billy Reid

My mom loved telling the story about how much I loved baseball. She said that when I was seven, I woke up the morning of my first Little League baseball tryout, looked at her, and said, “I have waited for this day my whole life.”

Man, I loved baseball as a skinny ass, bucked-tooth kid with a bad hair cut. My team was sponsored by Farm Bureau, and later Kent Trucking. The other teams in Amite, Louisiana, where I grew up, were sponsored by banks and had rosters we feared. Our uniforms came with maroon and white trucker hats with a K on the front. Looking back, those were kinda baller, I have to say.

I couldn’t tell you how many games we won, and I can’t recount very many specific moments. What I do remember is playing. Riding our bikes to practice, hitting rocks in the front yard with our bats, just playing.

Many years later when my son, Walton, took an interest in baseball, I couldn’t wait to coach his team. The other dad-coaches and I did our best to keep it fun, but I know there were times when the winning overtook the playing.

I could tell the boys were scared to make mistakes, that they feared some parent might yelp at them from the stands, or a coach might get angry and bench them. My goal was to eliminate that fear. The other coaches and I would say, “Don’t go Gumby on us.” It meant “Don’t just put your head down and pout.” Our motto became “Next Play.” You made a mistake? OK. Everyone makes mistakes. Move on to the Next Play.

Eventually, the winning, the working toward a college scholarship, the traveling, began to overshadow the play aspect of baseball for Walton. All the wonderful times together began to feel more like “have to” times. “I have to work on my swing.” “I have to work on my footwork.”

Faced with the decision to play baseball in college, Walton said to me, “I don’t want to play anymore. I want to have a spring break. I want to be able to hang out, do other things.” My first thought was how can you do this to us? His baseball career—the long drives, the times between games when he hung out with his friends, playing—was also our time together. But he was looking forward to his Next Play, just like I’d encouraged him to do so many times on the field.

I’m a few years removed from our shared life of intense baseball, and I do miss it. I miss hitting fly balls and pretending to make Willie Mays catches in the backyard, jump throwing like Jeter, wiffle balls lost over the neighbor’s fence, tree bases and ghostrunners, popcorn, snowballs, sunflower seeds, and if I’m being honest, the teenage-boy diet of pizza, wings, and chicken fingers.

We dragged our daughters along too, and to this day they tell us those long drives and long hours at the Florence Sportplex are some of their best childhood memories, memories of being together as a family.

To any parent who spends countless dollars and hours on helping a sports-driven child improve in order to stay in the game: Try to remember that it’s really about the time together, the laughs and memories more than the hits, misses, and homeruns. There’s always a Next Play.

FIRST IDEA, BEST IDEA

Words by Adrienne Antonson + Photography by Rinne Allen

Our house hums.

With scooter wheels on the floorboards, singing echoing down the hall, and a trail of cornstarch leading to Edla’s newest recipe, the rooms shift constantly—repurposing themselves to match our moods and curiosities.

We live inside an ongoing experiment—one that prioritizes play, improvisation, and permission over perfection. Every corner has been rearranged a dozen times to make space for someone’s next idea. Our walls carry fingerprints and drawings. Our floors bear skateboard tracks. The home bends to meet us where we are: in motion, mid-thought, halfway through something that might become something else entirely.

After my divorce, when the dust of rearrangement was both literal and emotional, I transformed a newly available closet into something I’ve always dreamed of: a walk-in costume wardrobe. It’s a portal, really. Masks and wigs hang beside sequined robes; drawers overflow with fake teeth, prosthetic noses, and elegant gloves; crates of strobe lights and fog machines wait patiently for their cue. It’s our household’s shared language—and, I’ve realized, my love language, too.

When the moment strikes, we transform. The children know the power of a good performance—that the request to stay up late stands a better chance when paired with a handwritten sign that says I’m Not Tired, held by Humpty Dumpty in a hoop skirt. How can I say no to that?

A few years ago, I returned to my sculptural work with a new game: First idea, best idea. If my mind says blue, I reach for blue. If my first thought is tall, I build tall. It’s a quiet rebellion against overthinking, a way to move forward before doubt catches up. There’s honesty in honoring intuition, a kind of purity that feels like play. The result has blown me away: work I’m proud to make and excited to explore.

Lately I’ve been learning more about how our family’s brains work—the neurodiversity, the hypersensitivity, the endless loops of curiosity. A book I recently read (ok, listened to) described on-ramps: gentle entry points that help us begin difficult or mundane tasks. Music can be an on-ramp to cleaning. Dancing in the kitchen easily turns into putting the dishes away. Driving to the carwash with a caravan of friends transforms that tedious chore into a party. On-ramps are little tricks to unstick ourselves, where movement and joy lead to productivity.

What I keep circling back to is this: fun is our language. It’s how we connect, reset, and create again. It’s not the reward after the work is done—it is the work.

The giant nesting dolls in the yard, the resin and plaster on the porch, the half-painted walls—all evidence of a house that’s thinking, dreaming, and trying. That’s the kind of magic I want to live in. It’s not about polish, it’s about pulse—about staying close to that first idea, the spark that says this, now, go.

And so we do.

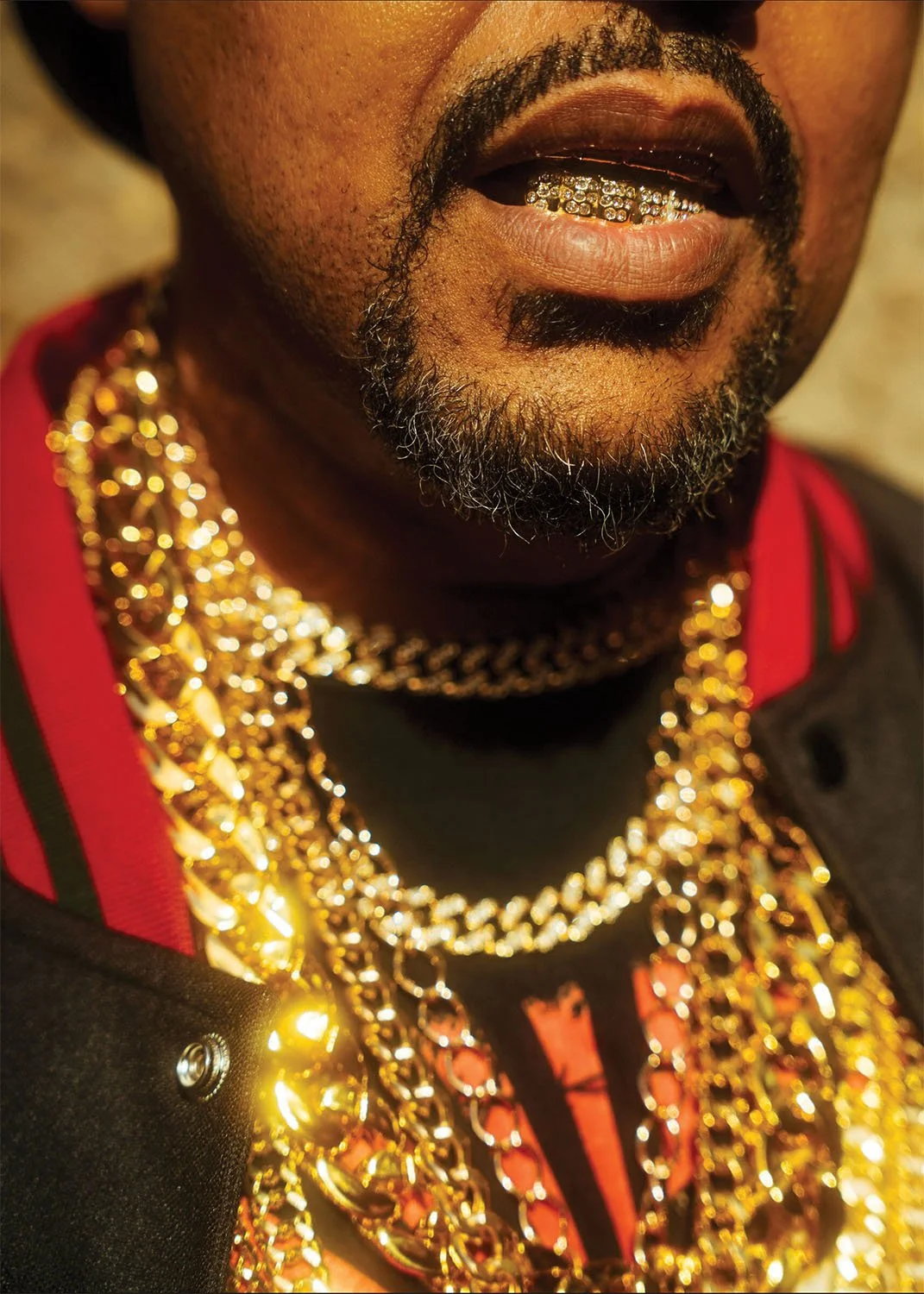

ALL FOR THE SAKE OF THE SHAKE AND SPARKLE

By Sara Beth Go

I didn’t really care about country music until Tim McGraw recorded one of my songs. But that’s the end of the story.

I grew up around color and drama. From my mother’s flirty pink wallpaper in the downstairs powder room where I performed scenes of my own productions in the mirror, to the 12-foot-tall, thick yellow living-room curtains that became props for my sister and me to twirl in and out of as we sang “The Sign” by Ace of Base.

My neighbor, vampire author Anne Rice, rode in a big black coffin inside an old-time horse-drawn hearse to make an unforgettable entrance to her book signings. St. Charles Avenue was four blocks away from the home I grew up in—we walked down ragged cement sidewalks, destroyed by live oak trees whose roots were as dramatic as I was.

We were just a hop, skip, trip, broken appendage, and jump away from the Mardi Gras route, where the rhythmic thunder of the bass drum, followed dangerously close by a swinging sousaphone, made my heart pump purple, green, and gold into every organ. My dad threw shiny beads from floats on wobbly wooden wheels. It killed his knees but it made the tinsel shake and sparkle. Neon-painted floats carried old men in jester costumes and masks, knees holding on for dear life, all for the sake of the shake and sparkle. This story starts when I lost my shake and sparkle.

In my early 30s, the odds of my anticipated music stardom were rapidly dwindling. My high school yearbook stated “In 20 years Sara Beth Geoghegan does for Christian music what Enrique Iglesias did for Latin music.” Only one of us was bailamos-ing, and it wasn’t me. I honestly thought it was just a matter of time before I was discovered. Time flew, but I didn’t. I was as far from the sky as I could be, grounded in the embarrassment of what felt like 15 years of failure. Shame is a cruel thief of all things colorful.

I was hospitalized three times. The first at a fluorescent-lit whitewashed hospital with a therapist that cared more about her lunch break than starting group therapy on time. I turned to introduce myself to the man next to me on my first day and noticed a deep scar across his neck. We carried different flavors of severe depression.

The second hospitalization was at a swankier joint in Arizona. I fell for another patient who was married. Turns out our common bond was debilitating anxiety from family trauma, and love addiction (no shit).

The last was due to the songs and numbers screaming in my mind that I couldn’t quiet. I spent Christmas in a hideous brown cubicle with other patients paralyzed by OCD. Scott was my behavioral therapist and refused to reassure me. I hated him and bought him his favorite cookies after treatment because his asshole approach actually kind of helped. But honestly, what kind of monster “loves” Chips Ahoy!?

Between hospitalizations two and three I gave up the strangling chokehold on “making it” in the music biz and went back to school to become a mental health therapist. I studied and was drawn to Play Therapy which is when a kid processes the things they can’t communicate with words through play.

Play is an extraordinarily important language that most adults forget how to speak when they learn how to talk. I bought baby dolls and a toy medical kit. In play language, these are interpreted as nurture. Soldiers and weapons symbolize anger, and superheroes and dragons represent power.

I bought my toys at a thrift store. Jennifer, a top-of-the-class cohort colleague, shopped at toy shops in nice Nashville neighborhoods. One day, I snuck into her stash and rummaged around. I found a clunky boy with huge wooden feet wearing a striped shirt and jeans and a clumsy girl with a flowery skirt and the same wooden feet. I swear to God, my mother would have made curtains out of that skirt pattern and hung them in her formal living room if she could have. They both had bendable arms and legs and bangs made of red string. I felt drawn to them. And then I had an idea.

That’s how it happens, right? A big bang in the brain encompasses a lifetime of heartache and hope and all the memories in between. Rapid neurons fired and zapped while I squatted in that office over her box of toys. The images fell into place and I knew what had to be done. It was so quick and beautiful, like the shake and sparkle of tinsel on an old float with creaky wooden wheels.

I took my favorite painting off the wall, pulled my husband’s shoelaces from his shoes, found miniature houses and butterflies and fake feathery pampas from our office decor and Started. With marbles, rocks, a boy in a striped shirt and a girl in a flower skirt, I Started. With a capital S. Because Starting is as crucial to art as a sousaphone is to the marching band in a Mardi Gras parade. To Start something is to end something else. I was ready to end the painful relationship I’d created with my music and commit to the sacred act of befriending my gift and Playing.

The idea was to use stop-motion (something I’d never done before) to tell a simple story of relationship ups and downs. I imagined it sweet and sad, honest and visually DELICIOUS. I searched the App Store and found a free stop-motion app. Installed it. Opened it. Took a picture. Moved one of the feathery pampas a tiny bit to the right. Click. A tiny bit more to the right. Click. Repeat. Click. Mess up. Delete. Bring the boy in. Click. Repeat. Yell, “Nathan (husband) come see this, it’s so cool!” Butterflies. Scream at cat to get out of picture. Smile. Click. What have I gotten myself into? Click. Watch from the top. It’s only 19 seconds long?! Click. Repeat. THIS IS AMAZING. Click. Repeat. What the hell do I do next? Idea. Execute idea. Click. Repeat.

I was so present that I forgot about time. I forgot to eat. I even forgot I failed at music. And in forgetting, my body remembered the shake and sparkle that shaped my upbringing, which shaped what happened next. 965 pictures later, with 964 mistakes and maybe 963 more gray hairs, I released what I thought was the most stunningly beautiful 2-minute 42-second masterpiece, Long Togetherness.

Then I did it again. And again. And again.

Now when I perform live I play along to my stop-motion videos, projected onto huge screens. It’s kind of my thing. And though I’ve seen the stop-motions a million times, it’s an honor to hear how they impact viewers and listeners.

Ok now we’re at the end of the story. The part where I tell you about Tim McGraw. In November 2023, I got an email from his record label requesting publishing information for a song I had written seven years prior with two other songwriters in Nashville. It was “on hold,” which meant he was thinking about recording it.

“Hurt People” was released a few weeks later, the Tuesday before Thanksgiving. We celebrated with my co-writer Tom Douglas at his house the next day and I showed him the stop-motion videos I’d been making. I asked if I should try to make one for Tim’s song and he said “ABSOLUTELY! He will LOVE IT.”

Tim Mc-Frickin-Graw did in fact love the stop-motion I made and released it, with my permission, as his own. (And I got paid a pretty penny for it.) I’d written “Hurt People” at the time I’d felt most like a failure, but looking back, I realize I had to feel like a failure in order to learn how to Start and Stop (Motion) in a way that was completely and fully mine, a way that reflects my Shake and Sparkle.

NO DIVING

My summer of soda and swimming

Words + Photography by Amanda Greene

I press “play” on my lavender Sharp QT-50 Stereo Radio Cassette Player, then slip into the pool, feet first. I come to the Chastain Park swimming pool several times a week. Sometimes it’s thundering and the pool is closed. De la Soul’s 3 Feet High and Rising is the only cassette I bring with me. My mom drops me off and I swim laps in my favorite bathing suit, a neoprene Body Glove one-piece with a yellow plastic zipper that runs from the center of the bust down to my belly button. I keep it zipped all the way to the top.

It’s the summer before tenth grade and I recognize one of the lifeguards from school. He is in an unknown-to-me higher grade and goes by the name Steamboat. He and the other lifeguards notice me swimming laps by myself, freestyle on the outbound lap and breast stroke on the return, and they ask me to join the swim team. “I’m good, thanks.”

I try to act cool but the reason I don’t want to accept the offer is that I’m afraid of diving. The head-first motion into water is too much for me. One time I was cheered into doing a baby-dive off the side of the pool. I stood at the edge and compacted my body down into a crescent shape, hands and face as close to the water as I could get them. Then I just tipped forward, into the water. I didn’t like it.

There’s a Coke machine by the deep end of the pool. The lifeguards figure out that if you buy one soda you can keep pressing the buttons and more will come out. Like the whole machine can be emptied for 50 cents. This Olympic-sized pool doesn’t get many visitors. Some days I’m the only one swimming. There are more lifeguards than pool guests and as the summer progresses I get to be an insider with them. I’ll take two quarters over to the machine and get a Coke then another and another. I add some Sprites and Orange Fanta in case someone wants one. We toss the sodas in the deep end of the pool to keep them cold. They float in between the two diving boards, and one by one teenaged lifeguards pluck them out. I take breaks and lie on my towel—always in the same spot near the stone bathhouse, and I never wear sunscreen. I imagine myself slim and tan like Cindy Crawford.

Swimming is fun, and as I get closer to the edge of the pool I can hear my music, louder when my head is above water but still audible when I bob down for the forward stroke. In my favorite song, “Tread Water,” Posdnuos and Trugoy rap about a crocodile, daisies, a monkey, a fish, and a squirrel. Some of the animals in the song are facing obstacles or dangers: a hurt hand, not having enough food, the song refrain reminding them, “Always look to the positive and never drop your head / For the water will engulf us if you do not dare to tread / So let's tread water."